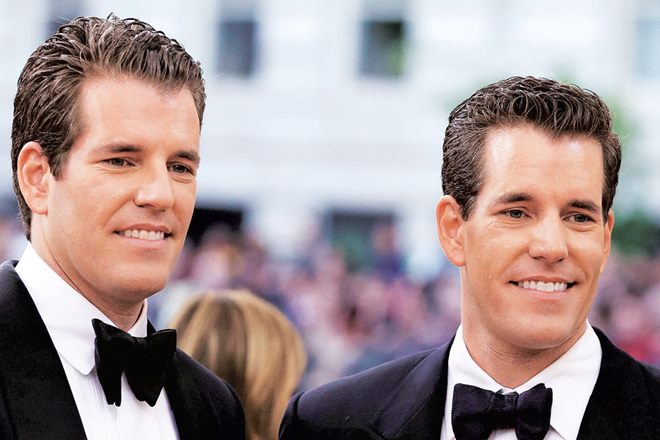

Is the Winklevoss twins vs Zuckerberg battle for Facebook really a one-sided story? A book attempts to achieve just that

Even before they bumped into Zuckerberg at Harvard, the Winklevoss twins were men of fortune.

Ben Mezrich’s three books have been adapted into movies, including the critically acclaimed The Social Network. No wonder, the American author’s latest work seems like a potential movie pitch. Bitcoin Billionaires: A true Story of Genius, Betrayal and Redemption is neither about bitcoins nor about billionaires. It is essentially about two brothers who, smarting from a defeat at the hands of Mark Zuckerberg, invested a part of the amount they got in their settlement with the Facebook founder in bitcoins early on. And when the bitcoins became a sensation in 2017, scaling dizzying heights in valuations, the brothers became probably the first-known billionaires of the cryptocurrency mania.

Even before they bumped into Zuckerberg at Harvard, the Winklevoss twins were men of fortune. And they had an idea potentially worth a fortune, far more than they were born into. They shared it with Zuckerberg and hired him to do some coding for the new site they were planning to roll out; instead, he set up Facebook allegedly by using the idea. Aghast, the brothers—Tyler and Cameron — dragged him to litigation. Although the Facebook founder argued he had used his own code to set up the giant social network, he settled the matter for $65 million when it was clear that the allegations, backed by scores of email exchanges between him and the brothers, could get him into a protracted legal battle.

But is the brothers’ investment in bitcoins a reflection of their true belief in the cryptocurrency? Not really. In their own words, when they invested in it, they thought it could be “either complete bullshit or the next big thing”. In fact, they wanted to start careers as venture capitalists but were sort of forced into the bitcoin investments when they realised no one would “take their money for fear of alienating Zuckerberg”. They used part of the settlement money to buy 1% of bitcoins in circulation for $11 million in 2011 and by late 2017, when the price of the cryptocurrency moved past $10,000 each, their total investments were worth $2 billion.

So, at best, it was a wager that paid off handsomely and they became accidental billionaires. But this is no redemption, as Mezrich would like to put it. If at all the brothers truly believed in something, it was in the inevitable surge of Facebook and the idea behind it. That’s why they insisted on having $45 million of the settlement amount in Facebook stocks, despite their lawyers’ reluctance. (In fact, they wanted the entire $65-million settlement amount in stocks but the lawyers demurred).

But why Bitcoins in the title? Probably because the author thinks while a social network like Facebook was the last big thing, Bitcoins would be the next big one. So, keeping it in the title will easily draw attention. Plus, Bitcoin billionaires has a certain ring to it. Ironically, the book hits the stands when Facebook is planning to launch its own cryptocurrency in early 2020.

But in the absence of solid substance to span a 276-page book, Mezrich seems to have relied heavily on style, giving this non-fiction a strong literary touch usually seen in fiction. The book becomes a movie pitch in its frequent over-dramatisation of tiny details, aimed at making a cinematic impact. This takes the shine off the subject that would potentially have been more engrossing without it. Certainly, it pales in comparison with his earlier book on the founding of Facebook, The Accidental Billionaires, which formed the basis of the movie, The Social Network.

Mezrich’s book acts as a defence of the Winklevoss brothers, who have been described as “identical twins, Olympic rowers and legal foils to Mark Zuckerberg”. It dwells upon their frustrations at the “betrayal” by the Facebook founder and subsequent struggle — both internal and external — to cope with what they thought was theft of their grandest idea. One can’t help but feel sorry for the brothers and empathise with them, given their vilification by a section of the US press. If that’s the sole intended purpose of the book, it has succeeded. If not, which is what it looks like, Mezrich should have tried harder.

Zuckerberg once said he was “going to fuck them probably in the ear”. And he did it more than once — first he set up Facebook, and then handed out a settlement that is peanuts compared with the wealth Facebook has generated for him. For the Winklevoss brothers to get back at him with vengeance and redeem themselves, it would certainly require more than just an accidental investment that propelled them to the billionaires’ club.

Mezrich’s damning of Zuckerberg (one whole chapter deals with this) may magnify the readers’ scorn for Zuckerberg but it doesn’t automatically grant redemption to the Winklevoss twins. Because they have to earn it.